A Jell-O Salad Revival: Is Grandma’s dark horse ready to ride again?

I was ready to unleash the demon. Kiley started filming, as I gathered my confidence. I placed a plate over the mold, and awkwardly squatted to heft the whole thing up. It wasn’t particularly heavy; it just felt alive.

“Ok, ok, here we go.” I said.

In a flash, I flipped the mold over and set it back down on the counter. Nothing. No sound of gelatin being released from it’s prison. No rewarding THUNK of the beast being freed. The demon I was scared to unleash was staying on it’s leash. This demon was toying with me.

“Ok, lets not panic.” I said, panicking.

“Maybe try using an offset spatula?” my friend Brandon piped up.

“Yeah! And here’s some hot water!” offered Kiley, filling up my sink with boiling water.

“Right, right, that’s smart.” I said.

I wedged my metal offset in between the walls of the mold and the gelatin, so air could rush in the next time I flipped the mold, and help push the demon out. After 30 seconds of that, I dipped the base of the mold in the boiling water, and with the feeling of excitement in my fingertips, knew it was time to try again.

“I’m flipping!” I said.

I flipped it again, and this time…it happened. I heard a plop and a squelch as it landed. The demon was free. My sweet, jello salad demon baby was free.

The hard work was done. All that we had left to do was to spank the thing with a spoon and tell the internet about it, because the internet is now passionate about gelatin.

But…could we be passionate about eating them again? Will chef’s tasting menus start showcasing seasonal vegetables bound in aspic? That’s what I need to know.

Why Was the Past So Excited About Jell-O Salads?

Many church basements are proof that Jell-O salad hasn’t completely gone out of style, but the dish no longer holds the lauded center-of-the-buffet-table status it used to. It’s been demoted to a cultural oddity, often an article of disgust, and even more often relegated to “grandma food.”

Hence, my curiosity.

Around the turn of the 20th century, a perfect storm was brewing to lead to the rise in popularity of gelatin-based foods.

Firstly, In 1889 powdered gelatin became a mass-produced convenience food by Knox Gelatin, and in 1900 the Jell-O brand was sold to Gennessee Pure Food Company who began an aggressive marketing campaign for the product. The convenience and consistency of a powdered gelatin made aspics and gelatin salads quick and exciting, instead of the week-long labor of love an aspic once was (gelatin sheets remained popular, as well, though they took a little bit more time for the home-cook than powder).

Inundated with the substantive advertising budgets of industrial food, home-cooks now stocked their cupboards with convenient, safe and affordable powdered gelatin.

Secondly, people were changing their minds of how they wanted food to look and how they wanted to make it. With the industrial revolution, homemakers were looking for products and scientific innovation to aid their work. Food historian Laura Shapiro explains in her book Perfection Salad, “…these women engendered a major domestic reform movement, which sprang up in the Northeast and spread rapidly throughout the country. ” She explains that this movement lead to the rise of domestic science, and the creation of the high school class we now call “home ec.” (Do high schools still have home ec? I actually have no idea.)

In conjunction with the domestic science movement, the end of the 19th century heralded the opening of the Boston Cooking School. It was founded to primarily teach housewives how to cook, and give them the modern, scientific answers they were looking for.

Aesthetically, the Boston Cooking School taught food to be “tidy” and, most importantly, “dainty.” This level of tidiness gave housekeeping and cooking a certain level of class and sophistication that middle-class housewives held as imperative in their kitchens.

Desserts were a ready target for gelatin: pulling up the rear of a long meal requires a light and decorative hand, which was made easier by colorful and curious gelatin. But ever the opportunist, gelatin found its way to the salad course as well.

Salads were quite problematic for this ideal of daintiness, since they were seen as, to quote Shapiro, “…nothing but a heap of raw ingredients in disarray” which “plainly lacked cultivation.” She goes on to explain that the Boston Cooking School teachers saw that the “…tidiest and most thorough way to package a salad was to mold it in gelatin.” No more sprawling leaves, or unkempt ingredients rolling around the plate.

The jello salad seed that was sown at the beginning of the century blossomed, and for over half a century, gelatin-bound salads, desserts, and appetizers were popular on dinner tables. Their ingredients ranged from vegetables, to fruits, to meats, to eggs, and they went inside of, well, anything you could keep still long enough.

The Internet Wants to See Your Jello

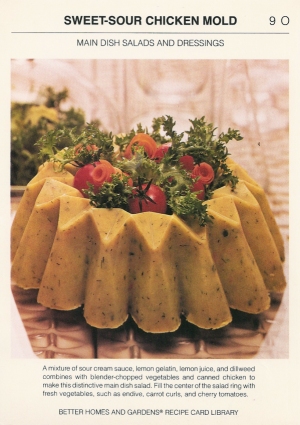

Even though they allegedly disgust us, our disgust must amuse us, because the attention paid to these old gelatin pictures is incredible (for example, I got the above picture from this Buzzfeed article.)

I got the recipe for my Garden Vegetable Salad from the Facebook group Vintage Recipe Cards, which has over 10,000 followers who spring alive when the admin drops a Hot Dog Jello Salad picture.

I ended up sharing my version of the Garden Patch Salad on my personal Facebook (I obviously couldn’t help myself), and a few of my friends reacted by telling me I had to share it to the Show Me Your Aspics Facebook – a 30,000+ follower strong group, brimming with jiggly posts. I very much wanted to immediately share it, but I wasn’t quite sure how serious the group was, and I’m not exactly in the business of food porn for food porn’s sake (not that there is anything wrong with that. Get your kicks where you can.)

My tune changed when I saw that Ken Albala was a member of the group, and an active poster. Professor Albala is a food historian and professor of history at University of the Pacific. I started following his blog after hearing him on the podcast Taste of the Past, but didn’t realize he’d been getting into aspics until I joined Show Me Your Aspics.

A friend had dared him to join the group, and then dared him to make a jello. “I almost never ate or made the stuff, in fact it’s the only food I wouldn’t eat as a kid!” He told me. “Then I got hooked, for no good reason.”

Albala created the “BLTini” last summer. The BLTini is cured pork belly, tomato and lettuce inside of a gelatin made with gin and vermouth. He was shocked by the response it received. It was shared thousands of times, and someone tried to claim the photo as their own (which in our content-rich era, having someone single out your photo for thievery is a mark of distinction for sure.)

However, people’s comments often centered around the word “gross”. It brought out the “amused disgust” I mentioned earlier – a feeling of which people are so ready to give to aspics. (Also, there must be a word in German for “amused disgust.” They usually are good at making compound words for compound feelings. Thanks Germans.)

Though, as Ken emoted on his blog, what could possibly be gross about all the ingredients of a BLTini? In a way, its a dream combination in a convenient format.

The Year is 2022. Are we eating jello salads?

Since I joined the Show Me Your Aspics group, I’ve realized that a lot of serious conversations about gelatin are happening. Yes, a lot of people just wanting to watch jiggling as well, but it’s not the only thing happening. People are sincerely curious about making delicious food with gelatin.

Albala predicts that we will see a resurgence of aspics. I had the opportunity to ask him why jello found such popularity in the early and mid-20th century, and why he thinks it dropped off. Here’s what he thought:

“I think it has to do with faith in technology and science and a willingness to embrace convenience foods, bright colors, exotica and odd food pairings. These alternate with periods of traditional, simple, homey, local, healthy food… We’re coming out of such a period now I think. So I’m predicting gelatin will come back.”

The theme of Albala’s work now is how food trends cycle, and what creates their ebbs and flows. He think we’re on the brink of a gelatin revival. (Follow his blog!)

He believes if we can get away from the “retro jellos and artificial flavored garbage” that we could start to make some really delicious and exciting foods. I am inclined to agree heartily.

With that said, however, I think there are many recipes from the past that could completely tread water in the contemporary world. I treated myself to a stroll through the old Boston Cooking School Cookbook (7th Edition, 1945) and my copy of Mrs. Rorer’s New Salads (1912) and found some worthy contenders for creation.

Here are my submissions for your consideration.

OH! But in full disclosure regarding the Garden Patch Salad: it was gross. Don’t make it without serious modifications to the recipe. Brandon said he liked it, but I think he was lying. It was gross.

For More Good Reading on Jello History

Jello: America’s Most Famous Dessert

A Social History of Jell-O Salad: The Rise and Fall of an American Icon